Sharing documents with a Rocket.Chat room in Sandstorm

By Jade Q. Wang - 13 Oct 2016

I’m sharing a pro-tip today because I like making sure that everyone gets the most productivity they can out of Sandstorm.

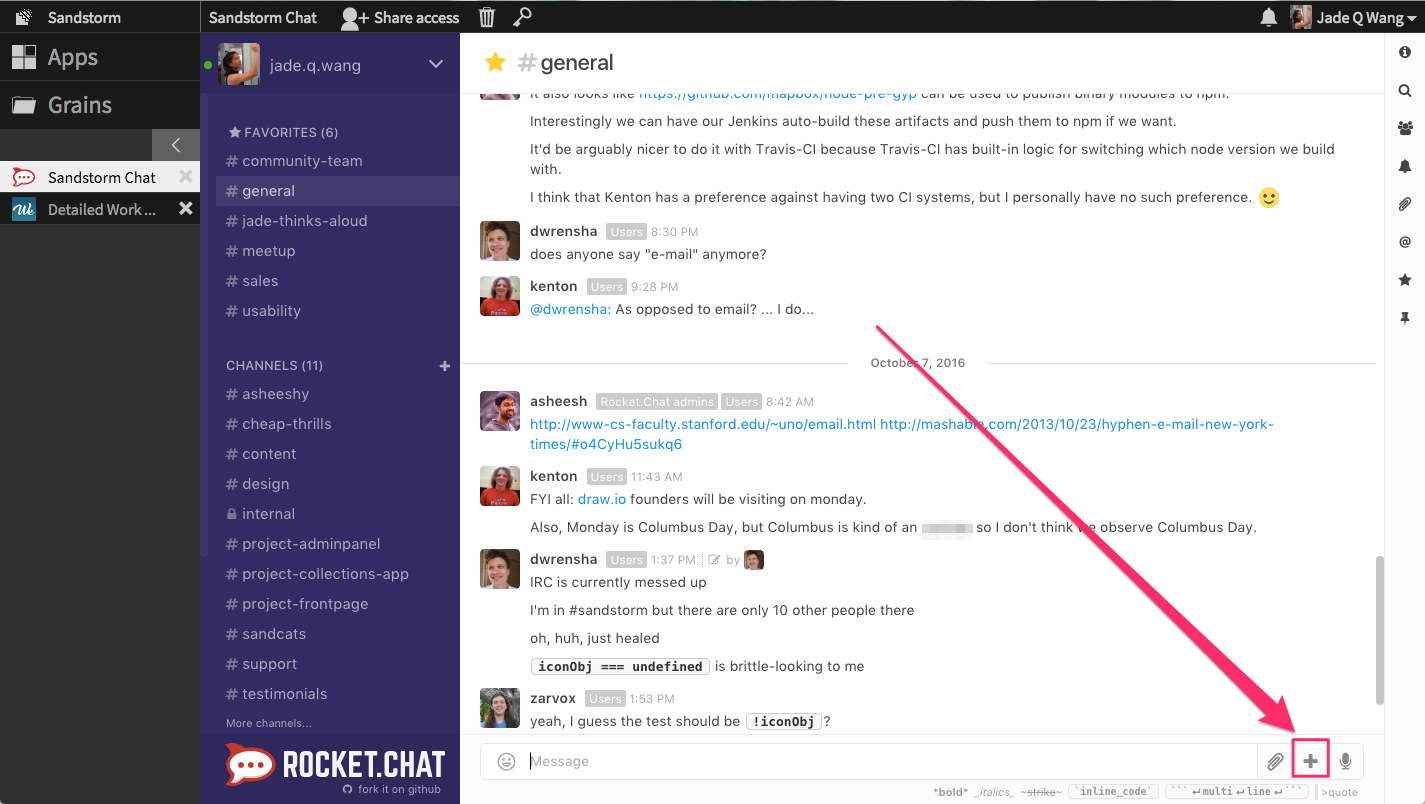

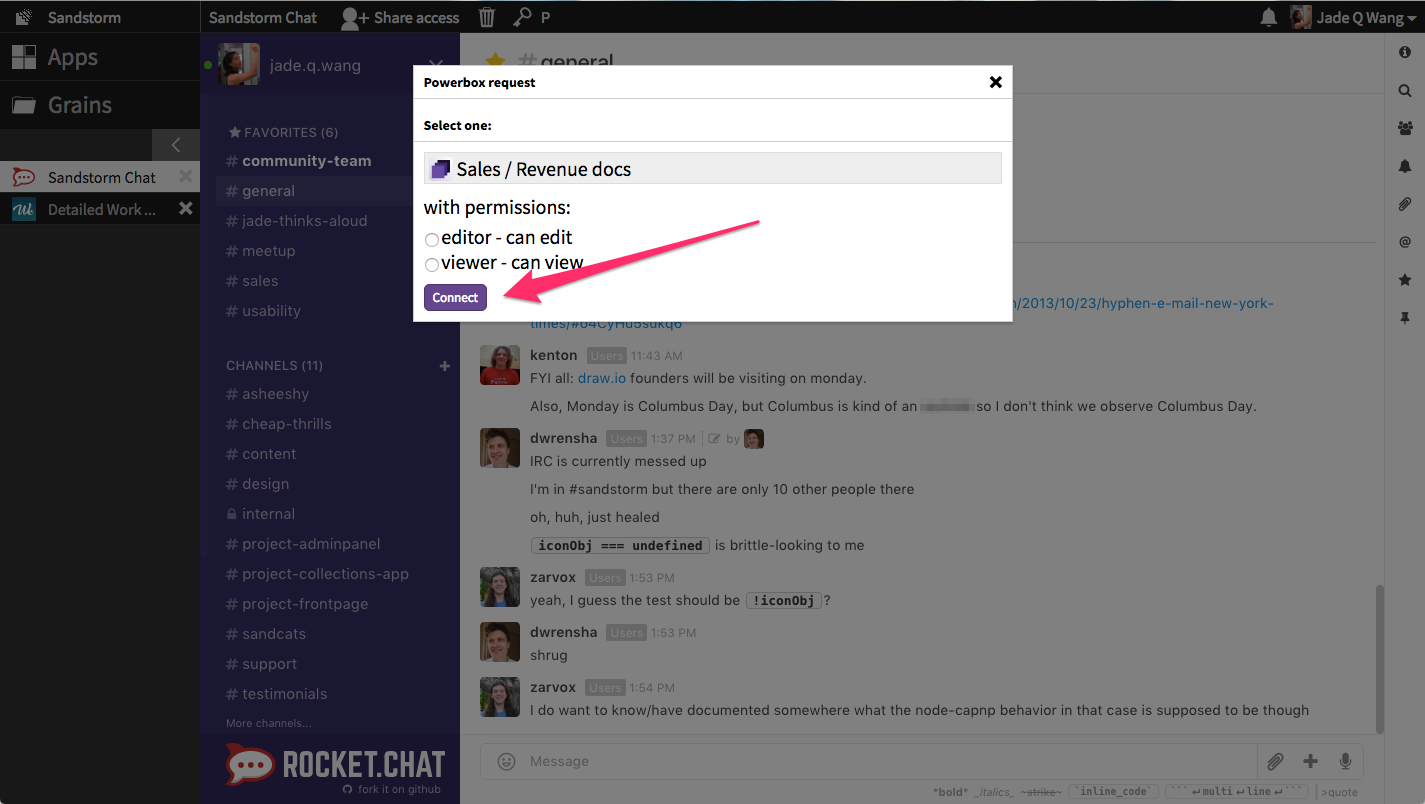

Let’s say I want to share a grain (e.g., a document, spreadsheet, git repository, or a Collection) with a group of colleagues who are already in the same Rocket.Chat chatroom. To do so, I first click the + icon in Rocket.Chat.

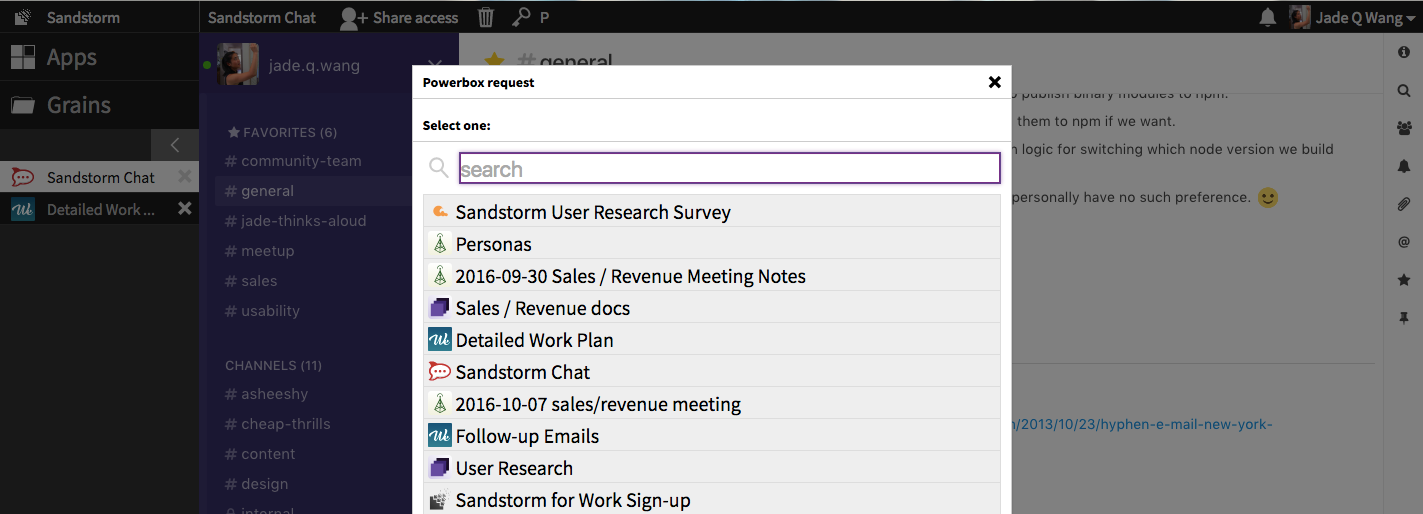

This opens a Powerbox request with a type-ahead search box. Before I’ve typed anything, I can see the grains that have most recently been opened by me.

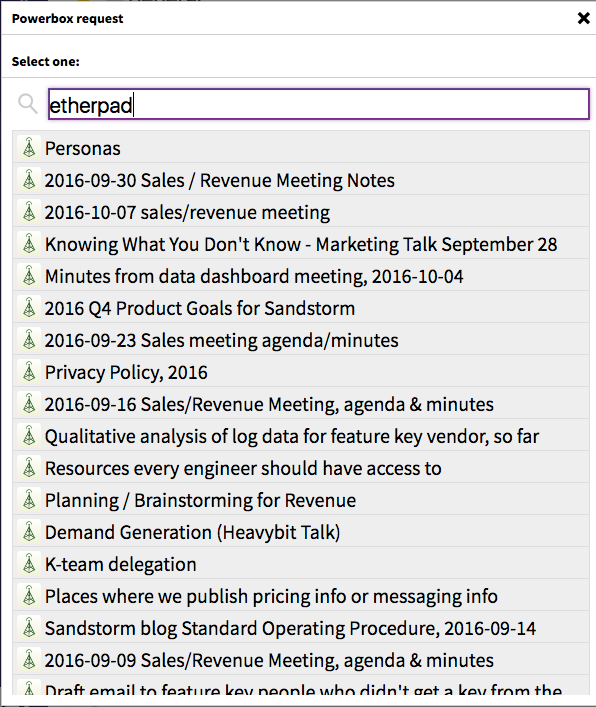

For instance, if I’m looking for feedback for a blog post I drafted in Etherpad, I can type “Etherpad” and it will list all Etherpads that I have access to on this server.

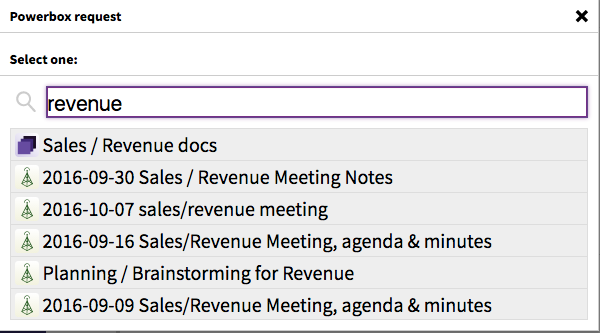

Here are all the Etherpads I have access to. But today, I’m actually searching for something else: a Collection titled “Sales / Revenue docs”. I can also search for grains by title, so I search for “revenue”:

Once I’ve selected the grain, I can choose whether I’d like to give everyone in this chatroom the permission to edit or only view this Collection before I connect the grain with this Rocket.Chat room.

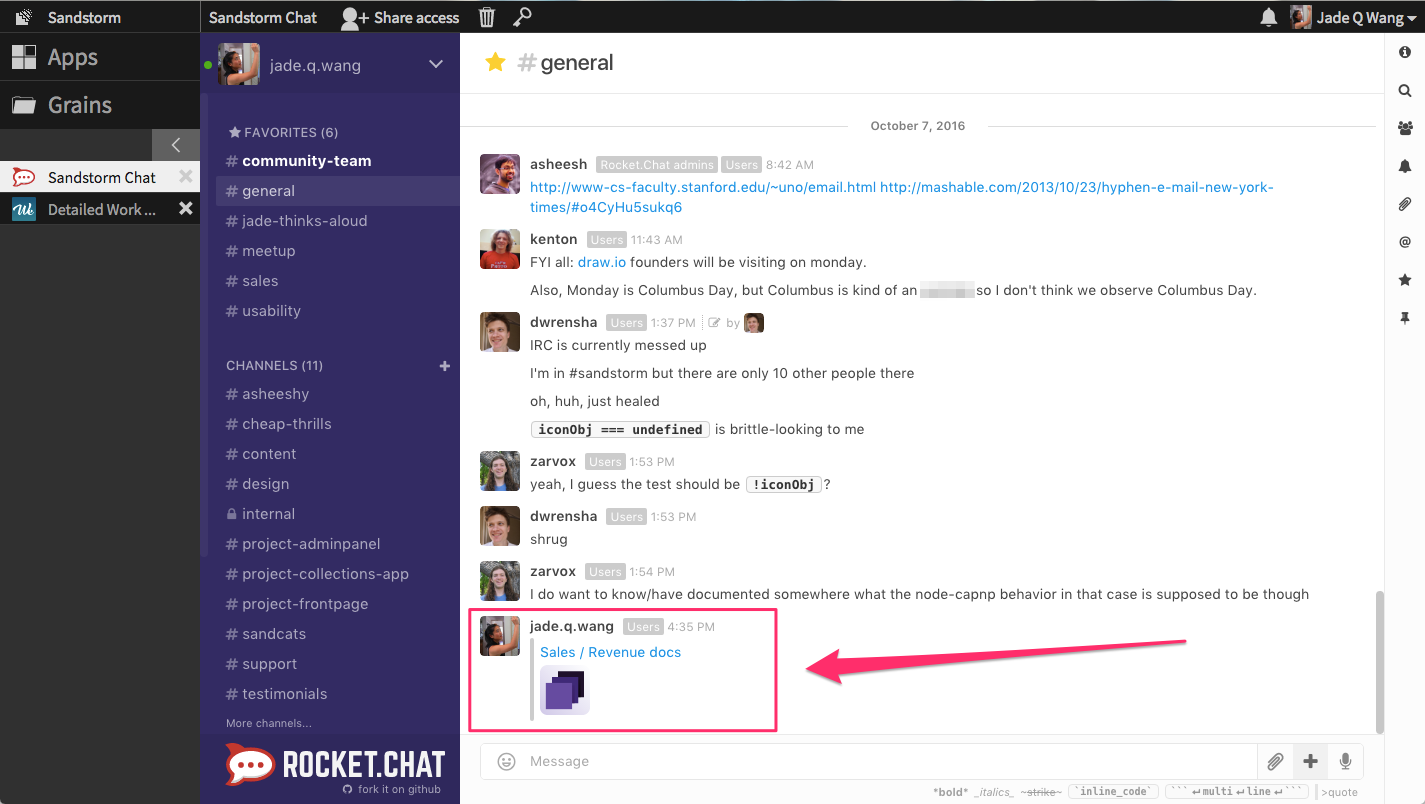

When I share a grain in a chatroom, it automatically renders a snippet which includes the icon for the app that opens the grain. It looks like this:

Now, everyone who is in this chatroom has access to this Collection (as well as every grain inside it). No need to go share it with them separately.

To try it out for yourself, go install Rocket.Chat now!

Do you use Sandstorm to collaborate at work? Sandstorm for Work (60-day free trial) comes with priority support, organization management features, and integration with enterprise infrastructure.

By the way, if you found this useful and would like to see more bite-sized pro-tip style blog posts in the future, please reshare this and let me know (I’m @qiqing on Twitter)!

The Mysterious Fiber Bomb Problem: A Debugging Story

By Kenton Varda - 30 Sep 2016

A month or two ago, we started seeing a mysterious problem in production: every now and then, one of our Node.js web server processes supporting Sandstorm Oasis would suddenly jump to 100% CPU usage (of one core) and stay there until it was killed. The problem wasn’t an infinite loop, though: the process continued to respond to requests, just slowly. Since the process continued to respond to requests, it continued to pass health checks and was never restarted automatically. But for users assigned to that shard, the service was essentially unusable, as every action would take seconds to complete. The problem left nothing at all suspicious in the logs – other than a gap in which far fewer requests that normal were being handled. At first, the problem only struck about once a week, seemingly at random.

This kind of bug is a web developer’s worst nightmare. How do you debug something which you can only reproduce once a week, at random, with real users on the line? What could even cause a process to slow down but not stop in this way?

What’s eating our CPU?

Obviously, we needed to take a CPU profile while the bug was in progress. Of course, the bug only reproduced in production, therefore we’d have to take our profile in production. This ruled out any profiling technology that would harm performance at other times – so, no instrumented binaries. We’d need a sampling profiler that could run on an existing process on-demand. And it would have to understand both C++ and V8 Javascript. (This last requirement ruled out my personal favorite profiler, pprof from google-perftools.)

Luckily, it turns out there is a correct modern answer: Linux’s “perf” tool. This is a sampling profiler that relies on Linux kernel APIs, thus not requiring loading any code into the target binary at all, at least for C/C++. And for Javascript, it turns out V8 has built-in support for generating a “perf map”, which tells the tool how to map JITed code locations back to Javascript source: just pass the --perf_basic_prof_only_functions flag on the Node command-line. This flag is safe in production – it writes some data to disk over time, but we rebuild all our VMs weekly, so the files never get large enough to be a problem.

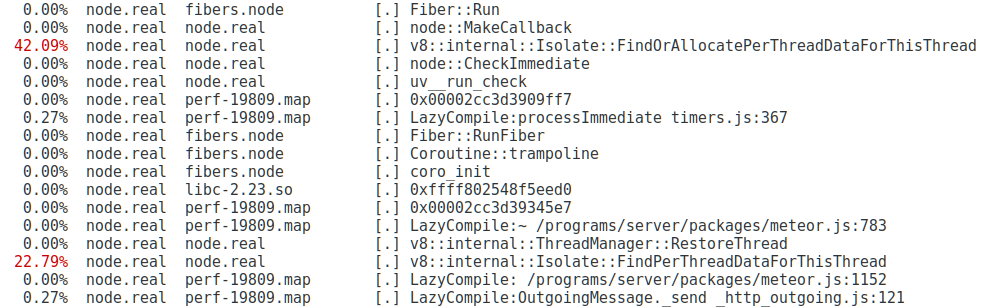

Armed with this new knowledge, we waited. Finally, after a few days, my pager went off. I shelled into the broken server, recorded a ten-second profile, restarted Node, and then downloaded the data for analysis. Upon running perf, I was presented with this:

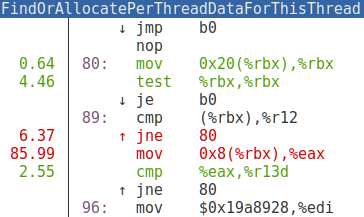

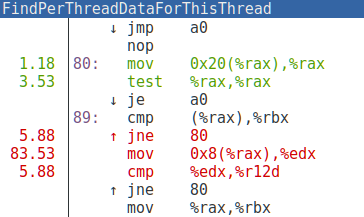

Well, this looks promising! Almost all the time is being spent in two C++ functions! The perf viewer makes it easy to jump directly into the disassembly:

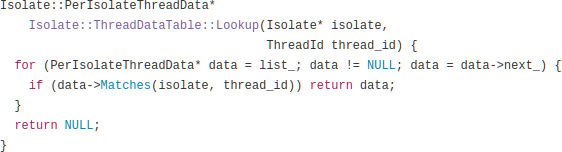

Wow! Almost all of our CPU time is being spent on a handful of instructions. In fact, what we’re looking at here is two different inlined copies of the same C++ code:

What you are looking at is a loop that traverses a linked list trying to find the element with a particular ID. We were spending the majority of our CPU time scanning one linked list.

V8 “threads” don’t scale

So, what is this code for?

You might be surprised to see the word “thread” in V8, which implements Javascript, a language known for being almost militantly opposed to threads. It turns out, though, that V8 supports “green threads” – simulated threads implemented entirely in userspace, with cooperative switching. Node users can take advantage of this via the node-fibers npm package. This package allows you to avoid Node’s “callback hell” by instead instantiating arbitrarily many call stacks and jumping between them whenever you need to wait for an asynchronous operation. Our code was, in fact, using node-fibers, mostly because we built on Meteor, which uses fibers by default.

The linked list in question implements a map from thread IDs to per-thread data, such as thread-local variables. Among other things, every time the process switches between fibers, the current thread is looked up in this table.

As any fresh CS grad knows, a linked list is not the ideal data structure for a lookup table – you probably want a hashtable, red-black tree, or the like. But as many more experienced engineers know, a linked list can be more efficient than those other structures in cases where the number of elements stays small. V8’s developers, as it turns out, had designed around the assumption of a fixed thread pool never containing more than a handful of threads. But node-fibers – especially as used by Meteor – doesn’t work this way. In Meteor, every concurrent operation gets its own fiber. Once a fiber completes, it is placed in a pool for reuse, but if many fibers are needed simultaneously, the pool can grow to any size. As the pool gets bigger, the linked list gets bigger, which makes fiber-switching slower, which makes the whole process permanently slower.

But what’s creating them?

But our processes weren’t getting slower over time. They were getting suddenly slower all at once. One moment the process is fine, the next it is hosed. Under normal load, our servers were sitting steady at around 100 fibers – nowhere near enough to be a problem. So now we had a new mystery: What was causing these sudden spikes in fiber creation? It was around this time we started referring to the incidents as “fiber bombs”. Alas, our profiles only showed us the after-effects of a bomb having gone off; they told us nothing about how the fibers were created in the first place. So we were back to square one.

Early on the morning of September 1st, the problem became suddenly more urgent: Instead of once a week, the problem started happening approximately once an hour. Like any good production problem, this began just after midnight. After three or so iterations of “get paged, wake up, restart the process, go back to sleep”, I grudgingly accepted that this could not wait until the morning. By about 5AM I had hot-patched our servers to monitor their own fiber counts and kill themselves whenever the number went over 1000 or so. In the process, I observed that a typical “fiber bomb” created anywhere from 5,000 to 20,000 fibers – all at once.

Still, the root cause was a mystery. With the servers now managing their own restarts and the pager quieting down, I crawled back into bed.

The spikes continued to happen approximately once an hour from then on. This was actually wonderful: it meant I could now iterate on the problem 150x faster than I could before! I began manually instrumenting the codebase with a sort of poor-man’s sampling profiler that specifically sampled fiber creation, and specifically did so at times when fiber counts seemed to be spiking. This turned out not as easy as it sounds, as there were many places that would create fibers as a result of some task having been queued previously. At the time of fiber creation, the queue insertion was no longer on the stack. So, I had to instrument the queue inserts too, and so on.

A bad monkey-patch

Soon, I made a startling discovery: It turned out that Meteor had monkey-patched the global Promise implementation. Specifically, they had apparently decided that they wanted .then() callbacks always to run in fibers, for convenience since most Meteor code requires that it be run in a fiber. Thus, they wrote code to intercept calls to .then() and wrap the callback in another callback that creates a new fiber and runs the original callback inside it.

This might sound basically reasonable at first (it should be “compatible” with standard Promise semantics), but there is a problem: In code that makes heavy, idiomatic use of Promises, it is common to string together a long chain of short .then() callbacks. As it so happens, Sandstorm itself contains a lot of Promise-based code, especially around communicating with its back-end, which it does using Cap’n Proto. Cap’n Proto’s API makes very heavy use of Promises, and does not expect to run in fibers. Thus, this code which seemingly had nothing to do with fibers was in fact the main creator of fibers in our system, creating massive quantities of totally unnecessary fibers, wasting memory and CPU time.

But even that didn’t actually explain the bombs. The way fibers work, if you start a new fiber that immediately completes, the fiber immediately goes back to the fiber pool. All of our Promise-heavy code operated in asynchronous style, therefore the callbacks would always complete immediately. So while the Promise code was needlessly starting lots of fibers, it should actually have been reusing the same Fiber object over and over again.

But there was one more wrinkle: It turns out that the V8 promise implementation itself sometimes calls .then() recursively, passing along one callback from one promise to another. In fact, it has to do this to correctly implement the spec. But since .then() had been monkey-patched, each time the same callback passed through another .then() call, it received another wrapper layer spawning another fiber. In the end, one callback, when finally called, would start a fiber, which would start another fiber, which would start another fiber, and so on. Since each fiber in this chain was itself responsible for spawning the next, all the fibers would be started before any completed. If one callback managed to be wrapped 20,000 times, then you get 20,000 fibers, all at once.

I patched the Promise monkey-patch such that, after wrapping a callback, it would mark the wrapped callback object with a field like alreadyWrapped = true. If the same callback came back to be wrapped again, the code would see this marking and avoid double-wrapping.

And just like that, the problem stopped.

Meanwhile, we’ve also filed an issue against V8, requesting that they replace their linked list with a hashtable. This wouldn’t have completely mitigated the fiber bombs, but it would have at least prevented them from permanently crippling the process.

August changelog: what's new in Sandstorm

By Asheesh Laroia - 13 Sep 2016

August’s most visible change is that when new users join a Sandstorm server, some apps are installed automatically. By default, and on Oasis, users can jump into Davros, Etherpad, Rocket.Chat, and Wekan, and they can create collections using the Collections app. The server administrator can choose which apps come preinstalled for their users. We hope this helps people quickly become productive with Sandstorm!

We made some underlying technical changes this month, too. The most significant is that we migrated to Meteor 1.4, which allowed us to switch to the most recent long-term supported version of nodejs, node 4. This required some substantial upheaval behind the scenes. It also enabled a change we’ve wanted to make for a long time: users of our sandcats.io free HTTPS service now use ciphers supporting perfect forward secrecy. If you test your own sandcats-enabled server on the Qualys SSL Labs server test, you’ll see that your grade has improved from an A- to an A!

Sandstorm servers have automatic updates enabled by default, so to get these updates, you don’t have to do anything. Sandstorm checks for updates and smoothly switches to the latest code every 24 hours.

Here’s the full August changelog!

v0.179 (2016-08-26)

- A user can now request deletion of their own account, unless they are a member of a Sandstorm for Work organization. Deletion has a 7-day cooldown during whith the user can change their mind.

- Admins can now suspend and delete accounts from the admin panel.

- Apps can now request that an offer template be a link with a special protocol scheme that can trigger a mobile intent, allowing one-click setup of mobile apps. Apps will need to be updated to take advantage of this.

- Identity capabilities now have a getProfile() method, allowing a grain to discover when a user’s profile information has changed without requiring the user to return to the grain.

- Fixed that admins were unable to un-configure SMTP after it had been configured.

- Fixed problems in sandstorm-http-bridge that could make notifications unreliable. Affected apps will need to rebuild.

- Increased expiration time for uploading a backup from 15 minutes to 2 hours, to accommodate large backup files on slow connections.

- Fixed email attachments from apps having incorrect filenames.

- Fixed various styling issues.

- Various ongoing refactoring.

v0.178 (2016-08-20)

- The grain list can now be sorted by clicking on the column headers.

- Many improvements to mobile UI. (Still more to do.)

- Your current identity’s profile picture now appears next to your name in the upper-right.

- Fixed desktop notifications displaying grain titles incorrectly.

- Fixed

spk publishthrowing an exception due to a bug in email handling. - Improved accessibility of “Sandstorm has been updated - click to reload” bar.

- When an app returns an invalid

ETagheader, sandstorm-http-bridge will now log an error and drop it rather than throw an exception. - Updated to Meteor 1.4.1.

- Oasis: Fixed appdemo not working for Davros.

v0.177 (2016-08-15) [bugfixes]

- Changes to SMTP handling in v0.175 caused Sandstorm to begin verifying TLS certificates strictly. Unfortunately, the prevailing norm in SMTP is loose enforcement and many actual users found Sandstorm no longer worked with their SMTP providers. This update therefore relaxes the rules again, but in the near future we will add configuration options to control this.

v0.176 (2016-08-13) [bugfixes]

- Fix web publishing to alternate hosts, broken by an API change in Node.

v0.175 (2016-08-13)

- Grain sizes now appear on the grain list.

- Added

sandstorm uninstallshell command. - Upgraded to Meteor 1.4 and Node 4.

- Sandcats: HTTPS connections now support ECDHE forward secrecy (as a result of the Node upgrade). Qualys grade increased from A- to A.

- Bell-menu notifications now also trigger desktop notifications.

- The collections app has been added to the default preinstall list for new servers. (We highly recommend existing servers add it in the admin settings, too.)

- No apps will be automatically installed on dev/testing servers (e.g. vagrant-spk).

- Switched to newer, better mail-handling libraries.

- Fixed the “close” button on the email self-test dialog.

- Fixed the “dismiss” button on notifications behaving like you’d clicked the notification body.

- Errors during a powerbox request will now be shown on-screen rather than just printed to the console.

- Fixed that uploading a backup left a bogus history entry, breaking the browser’s back button.

- Fixed powerbox search box, which was apparently completely broken.

v0.174 (2016-08-05)

- Admins can now choose to pre-install certain apps into new user accounts. For all new servers and Oasis, our four most-popular apps will be pre-installed by default: Etherpad, Wekan, Rocket.Chat, and Davros. Admins can disable this if they prefer, and servers predating this change will not pre-install any apps by default (but the admin can change this).

- offer()ing a grain capability now works for anonymous users, which means anonymous users can use the collections app. This app will be officially released shortly.

- Identicons are now rendered as SVGs rather than PNGs, which makes them much more efficient to generate. This in particular fixes the noticeable pause when the sharing contact auto-complete first appears for users who have many contacts.

- Updated to Meteor 1.3.5.1 (1.4 / Node 4 coming soon!).

- Fixed that Sandstorm sometimes temporarily incorrectly flashed “(incognito)” in place of the user name when starting.

- Sandstorm for Work: Non-square whitelabel icons now do something reasonable.

- Various refactoring.

- Somewhat improved styling of bell-menu notifications. (More work to be done.)

Sandstorm for Work is Ready

By Kenton Varda - 31 Aug 2016

Today, we’re announcing that Sandstorm for Work is no longer in beta. Companies large and small – ourselves included – have been getting work done using Sandstorm for months. It’s time for you to join us!

What is Sandstorm for Work?

Do you wish you could use web services like Google Apps, Slack, Trello, Dropbox, and others, but can’t for security, privacy, or compliance reasons? Frustrated by the setup and maintenance costs of most self-hosted solutions? Need to integrate with your corporate single-sign-on (LDAP, SAML, Active Directory) and enforce company-wide access control policies?

Sandstorm is a suite of web-based productivity software which you can deploy on your own servers with minimal effort. Any user can install the apps they need with a few clicks – like installing apps on your phone. Apps run inside secure sandboxes with single-sign-on and uniform fine-grained access control. And everything stays up-to-date automatically, so you can set it and forget it.

Sandstorm for Work is Sandstorm plus the ability to integrate with your corporate single-sign-on, priority support, and other features businesses need.

Pricing

During the beta period we listened to your feedback on pricing, and we’ve decided to make some changes:

- We’ve set a new list price of $10/user/month.

- For a limited time, we are offering an additional 50% off if you choose annual billing.

- Free trials now last 60 days.

Discounted and free keys

We only think you should be paying for Sandstorm if it is helping you make money. To that end:

- Non-profits with paid employees can receive Sandstorm for Work at half price: $5/user/month.

- Educational institutions supporting faculty and students pay $5/month for each faculty member and $1/month for each student.

- Volunteer groups can receive Sandstorm for Work completely free.

- Home users can also receive Sandstorm for Work for free; if you run an LDAP or SAML server for your own family, then we want your Sandstorm server to be able to take advantage of it.

- Bulk discounts are available for large organizations and resellers.

If any of these situations describe you, tell us about it and we’ll set you up.

Core productivity suite

Sandstorm now bundles our four most-popular apps. Every user can immediately edit documents with Etherpad, create task boards with Wekan, create a chat room with Rocket.Chat, and synchronize & secure their files with Davros.

On Sandstorm, these apps can integrate in ways that aren’t possible when they run stand-alone. For example:

- Activity, comments, and mentions are merged into a single notification stream, so it’s easy to keep track of what your teammates are working on across all apps at once.

- You can gather related data from across apps into collections to be shared as a unit.

- You can share data from any app directly and securely to a chat room in Rocket.Chat – click the button just to the left of the chat box. No need to generate nor copy/paste a secret link – and no need to worry about that link falling into the wrong hands.

- Sandstorm for Work’s priority support covers these apps in addition to Sandstorm itself. If you have a problem, just let us know and we’ll work with the upstream developers to get it fixed on your behalf.

Extended app library

There are currently 61 apps and growing available on Sandstorm, and you can easily make your own. Need to run surveys, create spreadsheets, make diagrams, take notes, typeset scholarly papers, host code, publish web pages, or run wikis? We have all that, and more.

Unprecedented security

Sandstorm is the only server platform that uses fine-grained containerization, which protects you against security bugs in apps, so you can safely let your users install the apps they need, relying on Sandstorm’s automatic exploit mitigation and network isolation to keep data safe.

Automatic updates

As always, once you’ve installed Sandstorm for Work, Sandstorm and apps will be kept up-to-date automatically, with no action needed on your part. Sandstorm is getting better every day, and your users will get those benefits without you lifting a finger.

Still open source

Sandstorm for Work is 100% open source software with a thriving community. That means it will never disappear or stop working. Read more in our original announcement.

Decentralization is about diversity

By Kenton Varda - 17 Aug 2016

Lately, there has been a flurry of activity around decentralizing the web. Summits have been held. New projects – and companies – have been started. Having worked on this issue for several years now, we’re excited to see it becoming increasingly mainstream.

But what, exactly, are we trying to solve? Most people think it has something to do with privacy, and maybe also security. Some argue that data ownership and mobility are the most important things. Sometimes this leads decentralization projects to focus on data storage while neglecting compute. Some projects even propose that so long as storage is decentralized, it doesn’t matter where the software actually runs.

Privacy, security, ownership, and mobility are all important, but I feel there is a much more important goal that is often poorly understood:

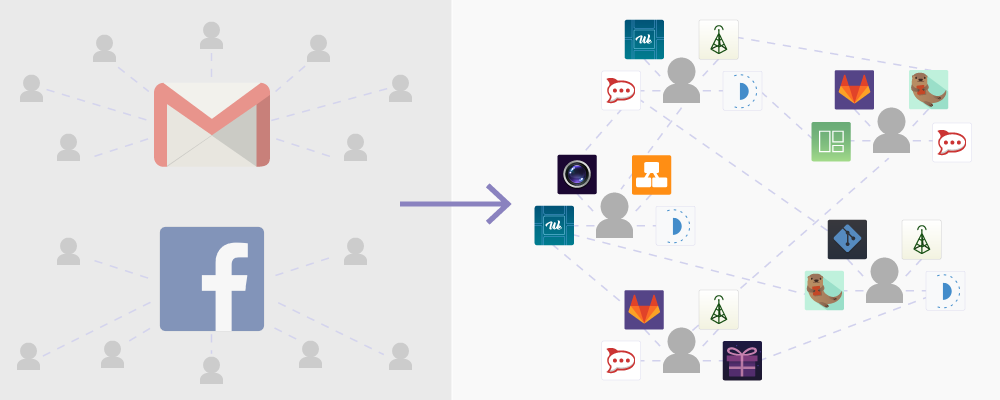

The most important reason to decentralize is software—and developer—diversity.

By “diversity”, I mean this: Who can develop software that other people can plausibly use? Is it primarily mega-corps like Apple and Google? VC-backed startups? Or can one random person, working in their spare time, build just the right app and reach millions of people? Can a community of unfunded volunteers build an open source app that wins because it is the best? Can an employee of one company, having built a useful internal app to solve a problem they had, give (or sell) that app to another company in the same position, without a lot of hassle? Can a teenage fan of a particular video game build an app that assists players of the game, and then share that app with the rest of the game’s community?

All of the above happens regularly with mobile and desktop apps, but it is far more difficult on the web.

We live in a time when our tools are so good that a single competent application developer working weekends can create almost any web application you can imagine. However, rarely can that single developer also run a secure, scalable service and a business around it. As a result, when software is delivered as a service, the only software that is available is that which was deemed a priori to be sufficiently lucrative to interest a mega-corp like Google or a VC-backed startup. Therefore, the only software services we get come courtesy of these gatekeepers. Experimental, indie, or amateur projects are rare. Novel services serving a small niche community are rare. Services designed by people who aren’t well-represented in the tech industry are rare. Community-driven open source projects basically aren’t viable.

The only way to solve these problems is by decentralizing the software (not just the storage). Software must be provided as a package – not as a service – with each user running their own private copy. It doesn’t really matter if the user chooses to deploy to “the cloud” or to their own machine, as long as they can run any package they want. It is, however, important that the means to deploy software be accessible even to non-technical users, so that everyone can participate and developers can reach a wide audience. Deploying an app on your server must therefore be as easy as installing an app on your phone, and must be “secure by default”.

This is the focus of Sandstorm.