ShareLaTeX: Collaborative scientific typesetting

By David Renshaw - 25 Jul 2014

Today we are releasing our port of ShareLaTeX, a real-time collaborative editor for typesetting scientific documents.

You can install it on your Sandstorm server now, or try it on our demo server.

LaTeX has long been a standard tool in the world of academic publishing, and we think that ShareLaTeX does a great job at making it more accessible and useful.

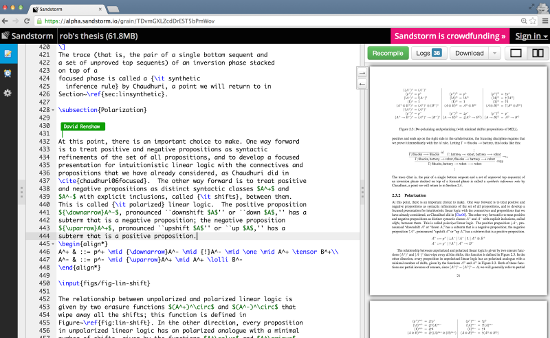

Using ShareLaTeX in Sandstorm to typeset Rob Simmons's PhD thesis.

We also think that, as an open source web app, ShareLaTeX makes a fascinating case study.

On the one hand, it’s hard to imagine any of the giant internet corporations ever offering anything like it, as its potential user base is probably not large enough to merit their attention. On the other hand, within its niche ShareLaTeX addresses a very real need – a need that’s certainly large enough to merit the attention of small teams of indie developers.

ShareLaTeX illustrates some of the barriers faced by such developers. Its core functionality consists of an in-browser editor and a server-side compiler, but to be a viable product it has had to do a fair bit more than that. ShareLaTeX also implements a secure login system, an interface for managing multiple projects, and a sharing model. Moreover, there is the question of hosting.

The striking thing about our port of ShareLaTeX is that it simply bypasses this non-core functionality. Sandstorm already handles login, already has a file selection and organization interface for managing multiple projects, and already implements sharing. The main changes we made to the ShareLaTeX code – and we did not in fact change very much at all – were to remove these features and delegate their responsibilities to Sandstorm instead.

Sandstorm, of course, also resolves the hosting question, making it easy for users to deploy ShareLaTeX to servers they control.

We take all of this as evidence that Sandstorm can eliminate many of the less-interesting and potentially costly parts of developing web apps. We hope that Sandstorm will enable developers to create many more apps like ShareLaTeX, catering to audiences of all sizes.

We now have an RSS reader; plus let's talk about security

By Kenton Varda - 24 Jul 2014

Have you ever wished for an RSS reader that won’t simply disappear if the developers get tired of it?

Today, we’re releasing our port of TinyTinyRSS to Sandstorm. Go install it on your Sandstorm server now, or try the Sandstorm demo.

Unlike traditional web apps, Sandstorm apps can never “disappear”, because they run on your server rather than on the developer’s. Even if the developer stops supporting the app, you still have a copy that will keep working.

You might say: “But what about security updates?” Good question! Let’s talk about security.

What happens if an app has security bugs?

It turns out Sandstorm apps are automatically much more secure than on traditional servers. Much of your security is handled by the platform, without the app’s involvement. In many cases, even an app that has known security flaws is perfectly safe to run in Sandstorm.

For starters, Sandstorm handles login and authentication, so automatically one of the biggest potential vulnerabilities is gone. There is no way someone can exploit a vulnerability in the app to “log in” to your account, and the app never has access to your password or session keys and therefore cannot leak them.

Moreover, attacks in which the attacker “tricks” your browser into performing some action on an app (with your credentials) are largely mitigated as well, because the attacker has no way to know your app’s address. Sandstorm assigns apps to hostnames on a temporary, per-session basis. When you don’t have your app open, it doesn’t even have a hostname. These hostnames are not displayed to the user, and we’re working on a change to make them cryptographically unguessable. If the attacker does not know your app’s hostname, they cannot launch CSRF attacks and many kinds of XSS attacks are thwarted as well.

The only remaining way to attack your app is by getting data into it by some other means. What this means depends on the app.

Imagine a document editor like Etherpad. This app never talks to the outside world at all. The only way an attacker can even talk to it (the first step in exploiting it) is by convincing you to explicitly share the document with them.

For an app like TinyTinyRSS, there’s another opening: the app requests RSS feeds from the internet and parses them. Hypothetically, a bug in the feed parser or in the way feeds are rendered in the UI could make the app vulnerable. In order to exploit such a vulnerability, an attacker would have to trick you into signing up for their malicious RSS feed.

But even in the worst case in these two examples, the damage is small, because Sandstorm itself isolates each app in a separate sandbox. Even if an app is exploited, the attacker only gets access to that app – and only the particular instance of that app.

In the case of Etherpad, we create a separate sandbox for every document. So, if an attacker exploits a document, they only get access to that document. And as mentioned above, there’s no way for an attacker to exploit Etherpad without first receiving a share from the document owner. And if the document has already been shared with the attacker, they already have the whole contents, so what’s left to exploit? They can’t use that exploit to get access to any other document, because each document is in its own sandbox.

In the case of TinyTinyRSS, if an attacker exploited an RSS parsing bug, they might get access to the TinyTinyRSS instance. This means they’d be able to see your other feeds, and could perhaps change your subscriptions. That’s it. For most people this is probably not a big deal. It’s a problem, but it’s nothing like having your password stolen or e-mail erased. And if you actually have a super-secret feed that you want no one to know about, you can protect yourself by having two separate TinyTinyRSS instances: one for your common feeds and one for the sensitive-but-trusted ones. If you accidentally sign up for an evil feed, you’ll probably put it in the first instance, and thus the sensitive instance is still protected. (Again, this is all hypothetical; we know of no such vulnerability.)

This is what we call the “principle of least authority”: Each app only has the “authority” to do its job, and thus a vulnerability in one app can only do as much damage as the app’s authority allows. On traditional desktop systems with no sandboxing, a security bug in one app could completely expose your entire system to hackers. On the web today, a security vulnerability in one app might expose your password, thus giving attackers access to any other app where you use that password. On Sandstorm, a security bug in one app only harms that app and things to which it is connected.

Of course, the above discussion is about apps. A bug in Sandstorm itself could be much more devastating. But that’s a smaller attack surface, and we have multiple security experts working with us. Security bugs are always possible in any code, but the less code you rely on not to have bugs, the less likely it is that one will harm you.

Ghost Blogging Platform on Sandstorm

By Kenton Varda - 22 Jul 2014

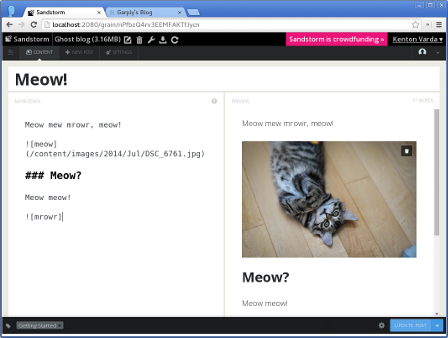

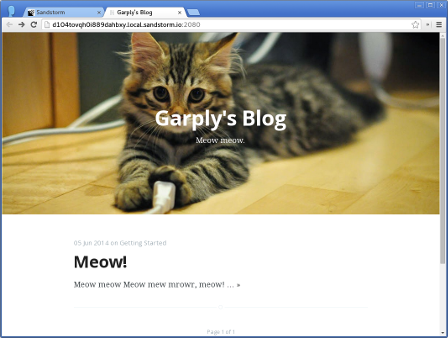

Today we’re releasing a major new app on Sandstorm: Ghost.

Ghost is a blogging platform featuring beautiful design, and which was funded by its own crowdfunding campaign last year. We’re extremely excited to bring it into the Sandstorm fold, in particular because we’ve been wanting to use it ourselves!

You can use Ghost on Sandstorm to publish a blog to an arbitrary domain. It uses Sandstorm’s web publishing features.

If you have a Sandstorm server, go install Ghost from the app list now. Don’t have one? Try our demo server.

Open Source Web Apps Aren't Viable; Let's Fix That

By Kenton Varda - 21 Jul 2014

The Motivation for Sandstorm

We talk a lot about the need for privacy, security, and control of your cloud data. Let me let you in on a secret: These aren’t the reason for Sandstorm. They are pleasant side effects.

The real motivation for Sandstorm is, and always has been, making it possible for open source and indie developers to build successful web apps.

In today’s popular software-as-a-service model, indie development simply is not viable. People do it anyway, but their software is not accessible to the masses. In order for low-budget software to succeed, and in order for open source to make any sense at all, users must be able to run their own instances of the software, at no cost to the developer. We’ve always had that on desktop and mobile. When it comes to server-side apps, hosting must be decentralized.

But today, personal hosting is only accessible to those with the time, money, and expertise necessary to maintain a server. Even most techies don’t bother, because it’s a pain. Sandstorm exists to fix that, making personal hosting easily accessible to everyone.

"The only solution is to make sure everyone has a server where they can install any software they want."

Open Source has worked on the desktop and mobile.

On my desktop, I run Debian Linux. My system is composed of several thousand packages. I have browsers, text editors, IDEs, chat clients, office suites, development tools, photo editors, and media players. Remarkably, every single one of these is open source. Even more remarkably, I can’t remember the last time I felt any need to use a non-open-source desktop app.

I’m no zealot. I don’t impose open source on myself, nor would I do so on others. I’ll use proprietary software when it gets the job done, and I have spent plenty of time as a Windows user and as a Mac user in my past, but these days I’m simply happiest on a Linux system. That’s my personal preference and it’s not for everyone, but the fact that this choice is available to me and that I can run an all-open-source desktop without pain is pretty amazing considering how things looked fifteen years ago.

Even Windows and Mac users these days use lots of open source software. By some measures, a majority of people now use an open source browser. VLC, BitTorrent, and other “indie” open source desktop apps are widely used even among non-technical people. Mobile seems even more full of open source and low-budget indie apps, as the various mobile app stores make it extremely easy for small developers to reach large audiences.

Yet, somehow, the web today is nearly completely devoid of open source software. Every day I use apps like GMail, Facebook, Twitter, Feedly, and others. None of these are open source. Granted, these apps often run on open source infrastructure, but that’s different. Most proprietary desktop apps use open source components and tools as well. But web apps, as the users see them, are almost invariably proprietary.

Why are all my web apps proprietary?

Open source web apps exist. For example, webmail apps like SquirrelMail and RoundCube have been around for a while. If you look hard enough, you can find open source online document editors, RSS readers, and even a few social networks. But even among techies, hardly anyone seems to use these, probably because they all require running your own server, and few people have the time, patience, and expertise for that.

There are a few success stories. Wordpress is open source and widely-used for blogging. But this seems to be the exception rather than the rule. And it’s questionable at that: most people who use Wordpress are not actually able to edit the code, because they are using it through a Wordpress hosting service and can only use the version of Wordpress that that host provides. Naturally, all hosts will likely only use the “official” version. So in practice, it’s almost not really “open source” but “visible source” – you can see the code and request changes, but you only get to use your changes if they’re officially adopted.

Why does no one use “indie” web apps?

Even on Windows, people commonly install little open source apps to get things done. Need to tag some mp3s? Want to connect to multiple chat networks with one client? Need to unpack a weird archive format? You’ll probably use an open source app. Sometimes it’s hard to build a business case around a niche purpose, yet little apps written by random people in their spare time are abundant. But on the web, it doesn’t seem to work this way. Any significant service with a server-side component can really only be run by a funded corporation.

Let me describe a case in point: I know a certain prolific coder by the name of Brad Fitzpatrick. You may know him as the author of LiveJournal, Camlistore, memcache, OpenID, and other things. But I want to talk about a project of his you probably haven’t heard of.

scanningcabinet is a little web app that helps you organize your paper mail. You drop your mail into your scanner, and the app scans it and uploads it to “the cloud”, where you can access, label, and search it later. Brad wrote this on a weekend several years ago and threw the code up on github.

This app could be useful to just about anyone. But sadly, no one can really use it. To set it up, you have to configure a server (App Engine, in this case) and deploy the code to it. Even for someone like me, who knows how to do that, it’s not something I really want to do.

By today’s model, if Brad wanted to make this app accessible to the masses, he’d have to run it as a service. He’d have to build in multi-user support, make sure it’s secure, deploy it, and monitor it. Worse, he’d have to pay for it, which means he’d have to monetize it, which probably means he’d have to start analyzing people’s mail to build advertising profiles, or set up billing. Brad obviously doesn’t want to do any of that.

And even if he did, who would use it? Do you want to upload your paper mail to servers run by some guy on the internet? I’m certainly not going to trust my personal data to any service that isn’t at least backed by an identifiable organization with something to lose if it screws up.

The problem is hosting.

By this point the problem is becoming clear: for open source software to make sense, the user has to be running their own instance. Software-as-a-Service and open source just don’t make sense together. It’s not really open source if you can’t run modified code, and the high barrier to entry shuts out hobby projects or anything unwilling to be monetized.

The only solution is to make sure everyone has a server where they can install any software they want. They don’t necessarily have to administer that server – it could be run by a friend, or a service – but each user must be able to install arbitrary software. And that software must be securely sandboxed to prevent buggy or malicious software from harming the rest of the server.

Today, this doesn’t exist in any practical form. Servers require time and technical expertise to set up, while turnkey hosting services only allow you to run a fixed set of software.

There is no place for open source web apps to run.

We’re making decentralized hosting viable

Sandstorm is a web app hosting platform that enables non-technical end users to install and run arbitrary software. Apps may be downloaded from an app store and installed with one click, like installing apps on your phone. Each app server runs in a secure sandbox, where it cannot interfere with other apps without permission.

We talk a lot about privacy, security, and control, but to me these have always been pleasant side-effects of Sandstorm’s model. My main motivation for starting this project has always been to enable open source software, hobby projects, niche applications, and indie developers. Even if each individual app in this category ultimately has a small impact compared to GMail or Facebook, the collective value lost by not giving these apps a platform is enormous. We need open source software to fill the niches that big companies aren’t interested in, and to push the boundaries they find too risky. We need software that can be tweaked without permission to try new things without starting from scratch. It honestly seems absurd to me that we don’t really have this on the web today.

Help us get there

We’ve already come a long way. We have a demo that does most of what we’re talking about already. But we’re coming up on the limits of what we can self-fund. We can get Sandstorm into production, but we need your help.

Please check out our campaign on Indiegogo, and spread the word.

We're Crowdfunding!

By Kenton Varda - 17 Jul 2014

Sandstorm is already working and useful (this very blog is hosted on it), but to get it the rest of the way to production, we need your help!